About Phyllis

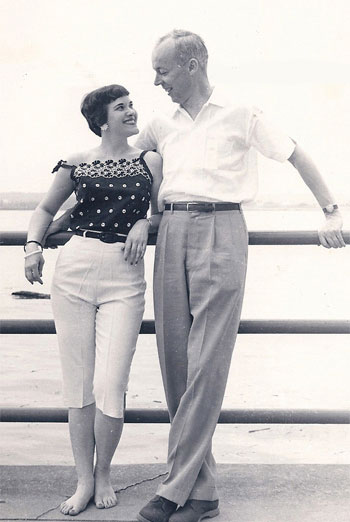

Phyllis and husband Rex

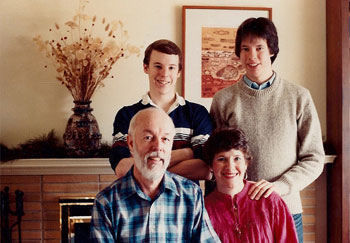

Sons Jeff and Mike

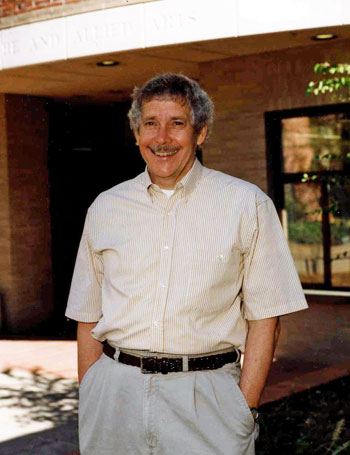

Brother John

I was born in Anderson, Indiana, in a tiny house on Chestnut Street that my dad and my grandfather helped build. It was still there, the last time I visited. I guess I was making up stories, not from the time I was born, but certainly as far back as I can remember.

In kindergarten, there was a wonderful teacher who sat down in the middle of the floor each afternoon and invited us to come to her and make up a story. She said she would write it down so we could take it home and show it to our parents. I only remember one of those stories I made up, but I do remember her saying, “Phyllis, you’ve had enough turns for one day. Let someone else have a chance.”

But my mom saved the first story I made up, and here it is:

Once upon a time, a little boy and a little girl lived in the woods with their mother. One day the little boy said, “Mother, I want an apple.” The mother said, “Okay.” The boy reached into the box, and the mother closed the lid on him, and cut off his head, and set him out in the yard and tied a rag around his neck to keep his head on. The little girl came home. She cried a lot. She sneaked out and pasted his head back on with magic paste. Then she put her brother in her boyfriend’s house. She grew up and married her boyfriend. The mother died. The end.

I’m sure that my parents were the inspiration for my loving to write, because they read aloud to us every night, almost until we were teenagers. It was just something my family did–The Wind in the Willows, Alice in Wonderland, The Bible Story Book, Grimms’ Fairy Tales… Mom and Dad read with great feeling and drama, and it was wonderful to snuggle up against Mom on the sofa, or sprawled out on the rug listening to Dad read Mark Twain’s books, my favorite, aloud.

Because I was born during the Great Depression, my Dad left college, studying to be a minister, and became a salesman for H.J. Heinz Company. My mother finished college about the time my older sister Norma was born. Five years after I came along, we had a little brother, John, the son my dad always wanted, and I was very jealous. Today, however, John, an architect, is one of my favorite people, and although we live across the country from each other, we are very close in our beliefs and politics, and are in frequent contact with each other.

Like most other people during the Depression, our family had very little money. When I began making “books” in fourth and fifth grades, they were drawn on the backs of “scratch” paper– discarded paper that had one side blank. I would staple the pages together, write my words at the top and draw pictures at the bottom. In sixth grade, the teachers in this rural elementary school decided to have an assembly to celebrate the principal’s birthday. My teacher asked if I would mind staying inside at recess to compose a poem to be read aloud at the celebration. It was the first time I had been asked to perform my own work, and I was both nervous and pleased.

The second time I was asked to perform my own work was as a freshman in high school. We were given the assignment to write anything at all to read aloud to the class as a creative writing assignment. It was December, and I wrote a long, funny poem about Christmas shopping and all the frustrations that go along with–overcrowded buses, people stepping on each other’s feet, and so on. I stood in front of the class and read it to much laughter, and the harder the audience laughed, the more dramatic my reading. In fact, the teacher was laughing so hard, I noticed, she had tears in her eyes. I had never had such a reaction before, and was more delighted than I could tell you.

But it didn’t last long. The teacher asked me to stay a minute after class, and when the others had left, she asked if I really, truly had written that myself or had copied it from a magazine. I was stunned. I told her that it was really, truly mine, but was so hurt I could hardly speak. She finally said, “Well, I’m giving you an A, because it really was very funny, but I’m adding a minus, because I’m still not sure it was yours.” I went on to be Senior Class Poet at our graduation ceremony, but it always bothered me that I didn’t have that teacher’s confidence.

As the middle child in the family, the younger sister, I was usually off by myself or with my friends, thinking up our own amusements. But when I became a teenager, it was my beautiful sister I wanted to be like.

I tried out, and managed to do, almost everything she tried out for and accomplished–I auditioned for the acapella choir, the madrigals, the operetta and the senior play. I made the choir, the madrigals, the operetta and the senior play. But my sister was also an artist, and I was never as accomplished in that as she was. She taught me how to use make-up, however, and better yet, how to play the piano by ear, even though we had both taken piano lessons. From then on, when I came home from school, I immediately sat down at the piano, and began picking out chords for the songs we heard most frequently on the radio–“I’ve Got You Under My Skin,” “Long Ago and Far Away,” “I’ll Be Seeing You,” and “The Man I Love.” I told my sister once, after we were both married and had our children, how much it meant to me that she taught me to play by ear, and she hadn’t even remembered she’d done it. When she died early of cancer, it was one of the saddest times of my life.

Both of us married young. She married her handsome high school sweetheart and started her family. I married even younger, right out of high school–once again, copying her. My husband was a University of Chicago grad student I met in our neighborhood. I had a romantic view of marriage, that it could solve anything, but four years later, when he suddenly showed signs of a serious mental illness, I realized it could not. I managed to get two years of junior college before I went to work myself–first as a clinical secretary at a University of Chicago hospital, then as a third-grade teacher on a temporary teaching certificate.

But in a futile attempt to find peace for my paranoid husband, we moved from place to place, supported only by the money I earned writing and selling short stories, and I finally borrowed money to admit him to an expensive hospital in Maryland. When it became clear that even this hospital could not help him, we divorced, and fifteen years later I wrote about these years in my nonfiction book, Crazy Love.

I met my second husband, the love of my life and the father of our two sons, at a church book discussion group. I was new to the church, and someone invited me to the book group, which met in members’ homes, and the night I attended, they were discussing Ibsen’s Doll House. I walked in the door, and there was Rex, and we both remembered noticing each other and feeling attracted. I’m not sure what he saw in me, because I hadn’t even read the book yet, but I liked his quiet manner–he didn’t talk until he had something important to say–but he also had a twinkle in his eye that I liked–the ability to see the humor or ridiculousness in something. He drove me home that night, and called me early the next morning to go out with him. We spent that whole afternoon just talking on a blanket in a park, then went out to dinner, and I knew I was in love.

I was very lucky that the job I loved most in the whole world, next to motherhood, was something I could do at home while our two boys were napping or in school. I sold about two thousand short stories before I started writing books, but once I wrote a novel, I was hooked. Although I never put my sons in my stories exactly, certain mannerisms or characteristics obviously found their way into some of my characters. I truly enjoyed being a mother. To me, it is the process of finding out who this little person really is–what his talents and skills are, his interests, and what he wants to become. Neither Rex nor I wanted our children to be “just like us.” Each of them selected fields entirely different from what we do–Rex was a speech pathologist working in government hospitals with servicemen and their families. Both of our sons are in technology, and have introduced us to completely different worlds from our own. Now we have grandchildren who are striking out on their own, expanding our worlds still further.

Phyllis on Twitter

Phyllis on Twitter

Alice's Blog

Alice's Blog

Phyllis on Facebook

Phyllis on Facebook